The Trade-Offs from Having Open-Ends in Your Survey

And what things makes people more/less likely to opt-in to your smartphone-related data collection

Good morning Friends. Happy Monday. Welcome to Pulse of the Polis 17. I hope you all had a restful weekend.

For those who are living in areas impacted by the often near (or actual) record-breaking heat: please be safe out there. A recent study found that the heat/humidity limit before healthy adults started exhibiting heat-related cardiovascular strain to be as low as about 90 degrees Fahrenheit, depending on the humidity (88F at 100% humidity, 95F at 70% humidity). Please stay cool and hydrated.

Let’s get going with today’s projects!

I’ve Got Two Projects for You Today

Today’s accidental theme is: It’s hard to get people into (and to stay within) your survey.

Increasing the Acceptance of Smartphone-Based Data Collection | Public Opinion Quarterly

One of the perennial challenges of survey research is mapping what people say that they do to what they actually do1. Fortunately, out of all the possible options, the technological dystopia we’ve landed on involves us carrying around devices which can potentially record virtually all of our digital lives—and most of our squishy, fleshy lives!—in exchange for the chance to look at memes and get angry at the opinions of strangers. Hooray!2

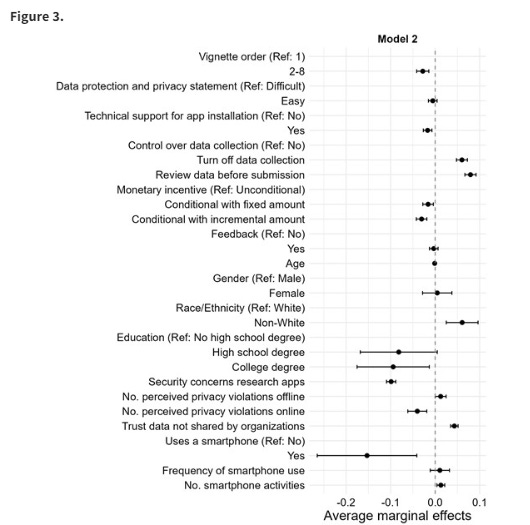

In all seriousness, provided that the information is gathered in an informed and ethical way, smartphone data (and other digital trace data) can be a valuable addition to other forms of data collection—and worthwhile information to analyze in its own right. This study published by Alexander Wenz and Florian Keusch uses a vignette experiment to see what factors are likely to (dis)incentivize people from participating in a study where academic researchers would gather their smartphone data. This experiment was fielded to nearly 1,900 members of NORC’s AmeriSpeak Panel, which is a probability-based panel, and each respondent saw 8 vignettes, each presenting an invitation to participate in a smartphone collection study with randomly varying elements. In each, they investigated the effect of having a simpler-to-understand data privacy statement, offering tech support to help with installing the tracking app, providing respondents with differing levels of control over what data ultimately gets shared, giving them a summary of the results, and providing an unconditional (e.g., $20 as a token of appreciation) versus conditional ($6 base and $2 per day/$20 provided they stick around the full duration) payments. Afterwards, they asked respondents how willing they would be to participate in the described experiment.

They found that, on average 44% of respondents said that they would participate in at least some of the described studies. Surprisingly, simplicity seemed to make some people less likely to participate—with simpler language incurring an average of 1.4 percentage point decrease and technical support incurring an average of a 3.4 percentage point decrease. Greater data privacy conveyed an 8 percentage point increase between the “no privacy” option and “review data prior to submission” options. Personal data summaries only increased reported tendency to join by 0.7 percentage points. Unconditional money incurred an average gain of 3.8 percentage points versus the lowest performing category ($6 to start + $2 per day).

There are a few things I want to especially commend the authors on. First, I love how they show the raw percentages of people who accepted the invitation to participate based upon the different conditions. To steal a line from my friend Chris Cyr: if an effect doesn't exist in the crosstabs, it probably doesn't exist at all. I love how they investigate subgroup effects—and I love how some of these didn’t pan out and they reported that anyhow!! That’s excellent science! I am also a huge fan of the fact that thy cite the individual analytical (R, in this case) packages that they used. These packages are often underrecognized contributions from their authors and teams; (at least in official scholarly merits). So kudos for citing them and passing along some of the credit! Very, very few of us who do quant research would be able to do what we do without the hard work of others translating statistical advances into reliable computational routines. (So, let me also take a sec to say, if any of such folk happen to be reading this: thank you—you're the best! ♥️)

There are a couple observations that I want to make that we should consider when observing these data though. The first is the number of people who express willingness to participate is extraordinarily high; way higher than I'd expect you'd actually see when testing this out. There are probably two parts of that. The first is exactly the issue I opened up the discussion with: These are self-reports. Respondents didn’t have to put their money where their mouths are and actually download an app3. That said, previous research does show decent correlations between stated intention and eventual actions undertaken. So while I expect some inflation due to that alone, it probably isn’t going to shoot the estimates all the way down to zero.

The other part, though, invariably comes from the fact that the people they are asking to participate in a fictional digital data collection project…are already participants in a digitally mediated survey panel! This doesn't just matter in terms of the overall numbers, which, again are high; but one could imagine how it would affect the average treatment effects as well. This is an incredibly tricky thing to avoid since you’ll likely have inflated percentages because the people who take surveys in general (and not just NORC online surveys) tend to be more likely to join-in on research initiatives anyhow.

The authors acknowledge both of these things in the limitations section of their paper. In the end, these issues are largely unavoidable for a project structured like this and I think that they do not eliminate the substantive lessons we gain from the study overall. I don’t disagree with their choice to use NORC at all; they went with a large, probability sample as a means of generalizing results to an audience that would be of significant interest to researchers who may want to conduct smartphone-based research: American adults. I think it was the right call, but I wish they had grappled a bit more with that large percentage of people signing up for the smartphone study and added some context to it.

That said, a big part of this might come from the fact that the source of the request was invariant across all conditions: researchers from a University. For both selfish and scientific reasons, I’d love to see what these rates would be if it were from a major company, or from a small market research firm, or from someone like NORC or Pew. Uptake rates may systematically vary across these different requesters.

All in all, super cool work! Here’s to hoping it inspires some folks to take it out into the field and report back what works when!

The Effects of Open-Ended Probes on Closed Survey Questions in Web Surveys | Sociological Methods & Research

Should something be an open-ended or close-ended response: that is the question4. Close-ended responses reduce respondent fatigue and satisficing and can allow us to make statements like “90% of people strongly agree that pineapple on pizza is horrible” with relative ease. Open-ends, though, are like us: sublime, insane messes that can only be categorized by accepting more edge cases than an emo music festival5. With the former, you get regularity but are fundamentally limited in what you can know. The other provides more depth but said depth requires more time and resources to analyze; and we’re often only interested in the in-depth perceptions of a subset of the sample anyhow. So what many researchers will do is have open-ends appear conditionally. You might get a survey where, if people say “yes, pineapple on pizza is awful” they’ll get a follow-up question that says “you said pineapple on pizza is awful. Please write a few words about how you came to this objectively correct decision.”

On the surface, this seems like a great middle-ground. Use close-ends to identify who you want to follow-up with more information and ask those folks selectively. It also follows a natural conversation flow; we often will say things like “what do you mean by [whatever it is you just said]” to signal deep, genuine interest in the topic and the interlocutors take on it. But is this strategy come with any costs?

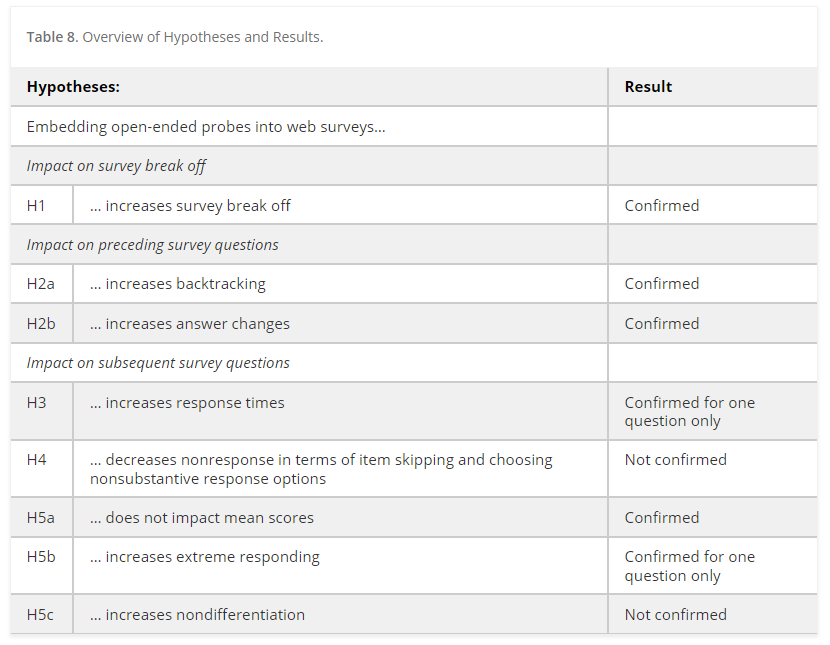

Of course it does. This is social science! There’s always a cost and trade-off to everything! In this research published in Sociological Methods & Research, Patricia Hadler fielded two nearly identical online surveys nearly 2,500 German adults (with respondents being randomly assigned to one or the other). In one, respondents answered questions on a variety of topics, including their political orientation, life satisfaction, and political cynicism. In one survey, however, each close-ended question was followed up with an open-end. It took a median of 17 minutes to complete the experimental condition and 16 minutes to complete the non-experimental condition. The research found that respondents in the open-end condition were more likely to backtrack to a previous survey question. Those who went back were substantially more likely to change their answers, presumably to try and prevent having to answer the open-end. They were also more likely to drop-off from the survey entirely, with female respondents being less likely than male respondents to drop out.

There is some good news though: The open-ends did not substantially effect response times to the subsequent close-ended questions (respondents in both conditions answered at more or-less the same clip)—nor were respondents more likely to skip questions or straight-line through. Respondents were also not more likely to give extreme answers to the close-ended questions and the distribution of responses overall were quite similar. Additionally, the overall percentages for the deleterious effects were relatively low: only about 80 respondents dropped out of the survey during Hadler’s instrument overall (though, of those, 65 were in the experimental condition).

What I love about this paper is that it immediately makes me think of more questions that I want answered in future work. Like, who are the kinds of people most likely to drop off and/or go back? The survey mentions gender differences, but is that all? How about older/younger people, political conservatives/liberals, those with higher/lower incomes—etc. Are the deleterious effects concentrated within the people who take surveys a bunch? What will happen to drop-off if the back-button is disabled? Are there different ways that we can word the open-ended follow-ups so that people drop off less? What if there were fewer open-ended probes? What if the survey were longer overall? Is the skipping due to it being a follow-up to the question or would people have dropped off when faced with any old open end? Will people backtrack if the question that prompted it is, like, 15 questions back compared to immediately beforehand? Will that cause more drop offs?

I’m sure I’m not the only one with these sorts of questions. I (and I’m sure other survey practitioners) have hunches informed by experience with regards to these and similar questions—but there are often difficulties collecting explicit data on them and disseminating the information to others. There is a far larger demand for this sort of “basic” research (in that it answers fundamental questions of interest to all sorts of practitioners; not in that it somehow takes less skill to pull off correctly) than I think is incentivized to provide. For one, our hunches are often wrong or carry caveats that we take as given until rubber actually hits the road. Second, sometimes we need to have some kind of research output (whether our own or from a reputable source) that allows us to tell particularly insistent and opinionated stakeholders “no, this is a bad idea. Please don’t make us do this.”

Thinking back to the article specifically: While there are definitely trade-offs to open-ends, it doesn’t seem like it will be that terrible. After all, the research here had open-ends after every close-ended question. That’s probably a lot more text data than the average project needs to implement. That said, if it is super expensive to collect respondents, it might be best to limit the number of open-ends that you ask to avoid excess costs and longer fielding times.

There are two things that, I think, limit the generalizability to this optimistic take though. First, this was performed on German adults. In my experience6, folks from different nations approach surveys differently: You might get more straight-lining in, say, India or maybe more drop-off in the United States. So I think more work should be done (and not just done, publicized) with similar set-ups in other contexts. Second, a big audience that would be interested in this are those conducting market research rather than social scientists. Are people more likely to respond favorably when being asked about their feelings on socially-important questions? Like, I’m probably more willing to elaborate every answer if I believe it will advance our state of knowledge—but I might even drop off if I got “You said that you used Lysol in the last year. Explain how you used it” when I’ve already answered about Mr. Clean, Bounty, 409, Dawn, Bissel, etc.7

I’m super glad to have read this article. I hope it gets cited a zillion times; it deserves it.

This problem is even harder, though no less important, when asking what people will do in the future

He said, primarily making creative outputs made using—and optimized for—cell phones.

Or, I guess, get money put where their mouths are since they’d be getting paid?

Literally.

Says the man click-clacking away with black nail polish and Escape the Fate playing in the background.

As well as being heavily documented in the survey literature.

I have pets and a toddler. We use a lot of cleaning materials in the house.